A few weeks ago I finished Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s much talked-about Americanah, the story of a Nigerian university student, Ifemelu, and her transplantation to the United States. I was so impressed while reading the book that I recommended it to my sister, Erin (whom some of you might remember from the post “Words of Wisdom from a High School Valedictorian“) who found a copy for herself and finished it in a record number of days. Despite a few flaws, mainly structural in nature, Americanah is a unique, thought-provoking novel that sharply demonstrates just how prevalent racism (still) is in America. Furthermore, there are seemingly few books written from the middle-class African immigrant perspective — or, at the very least, I am not familiar with many of them — which complicates the frequently recounted immigrant narrative focusing on economic and linguistic barriers to integration. Because we both enjoyed Americanah so much, and had so much to say about it, Erin and I decided to co-write the following review.

Overview of Book

By the time the story begins, Ifemelu has spent over a decade in America. Thirteen years, to be exact. Despite finding unprecedented financial and academic success by running a blog about race and racism, Ifemelu slowly comes to realize that there is “cement in her soul” and decides that she must return to Nigeria. Thus the visit to the hair salon to spruce up her appearance, where Ifemelu recounts her immigration story in flashback-style narration while sitting in the salon chair, waiting for the stylist to weave intricate braids throughout her hair. The flashbacks begin with an account of Ifemelu’s early life in Nigeria. Though she attended an excellent secondary school, her family’s lower-middle-class status put Ifemelu near the bottom of the wealth index of her classmates. Her father’s pompous vocabulary, deployed in an attempt to disguise the fact that he never attended university, and her mother’s religion-obsessed, neurotic behavior mean that Ifemelu’s parents are unable to transcend their class. Eventually, Ifemelu sees them as little more than a source of embarrassment. When, amid rising political instability and frequent shutdowns at the University of Nsukka, Ifemelu manages to obtain a visa to attend university in America, she does so with few regrets — the biggest being Obinze, her high school sweetheart. Ifemelu recounts just how pervasive dreams of America are in the Nigerian collective imaginary. School friends compliment each other by remarking, “‘You look like a black American,'” the highest commendation one can bestow (p. 67). Many of Ifemelu’s friends long to travel to the United States, where everyone has perfect teeth and nice clothes. Those who manage to get there are forever after christened “Americanah” due to the superior habits they acquire. This term, the namesake of the book, is explained on page 65. Ginika is one of the first of Ifemelu’s friends who manages to immigrate to America.

Ginika complained and cried, painting images of a sad, friendless life in a strange America…‘Ginika, just make sure you can still talk to us when you come back,’ Priye said.‘She’ll come back and be a serious Americanah like Bisi,’ Ranyinudo said.They roared with laughter, at that word ‘Americanah’, wreathed in glee, the fourth syllable extended, and at the thought of Bisi, a girl in the form below them, who had come back from a short trip to America with odd affectations, pretending she no longer understood Yoruba, adding a slurred r to every English word she spoke.” (p. 65)

The tacit understanding is that America irrevocably changes those who visit it, supposedly for the better. It is both a joke, a way to make fun of those who travel to the United States and return with haughty airs and strange affectations, but also a term of reverence that acknowledges the assumed prosperity of those who manage to make it to the ultimate first-world nation. However, as Adichie demonstrates throughout her book, the effect of Americanization on black immigrants in particular is more often fraught with tension, discrimination, and loss of identity. The following review will cover some of Americanah’s major strengths and weaknesses, paying particular attention to the way in which Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie complicates the immigrant narrative by integrating feminism, race, and satire.

Getting Lost and Becoming Black in America

The description of the immigrant experience in the United States is one of the strongest aspects of the novel. Ifemelu’s perceptive and insightful remarks about the realities of immigration are presented in stark contrast to the commonly held American belief that “Africa” is full destitute people, all of whom long to come to the United States in search of a better life. As a result, many of the people with whom Ifemelu interacts expect her to be grateful that the United States “allowed” her to immigrate there. Kelsey, an ignorant university student who Ifemelu encounters in the hair salon, is a perfect example how many people pretend to condemn America while secretly holding it in high esteem:

She recognized in Kelsey the nationalism of liberal Americans who copiously criticized America but did not like you to do so; they expected you to be silent and grateful, and always reminded you of how much better than wherever you had come from America was. (p. 189).

In reality, for Ifemelu, Nigeria posed significantly fewer problems in terms of race and identity. During a dinner party in her new home, Ifemelu lambasts a woman who claims that race is not an issue in her bi-racial relationship. As Ifemelu argues,

‘The only reason you say that race was not an issue is because you wish it was not. We all wish it was not. But it’s a lie. I came from a country where race was not an issue; I did not think of myself as black and I only became black when I came to America. When you are black in America and you fall in love with a white person, race doesn’t matter when you’re alone together because it’s just you and your love. But the minute you step outside, race matters. But we don’t talk about it… we don’t want them to say, Look how far we’ve come, just forty years ago it would have been illegal for us to even be a couple blah blah blah, because you know what we’re thinking when they say that? We’re thinking why the fuck should it ever have been illegal anyway?’ (p. 290-291).

Indeed, race is not a problem in Nigeria. Despite its spectacular economic gains, or perhaps because of them, American culture and society has failed to cultivate a sense of equality that transcends racial boundaries. After moving to the United States, Ifemelu has an extremely difficult first few years, during which she suffers from a loss of identity, the result of a social construct that paradoxically denies and emphasizes race. In one of her spirited blog posts (constituting some of the best parts of the novel), she states,

Dear Non-American Black, when you make the choice to come to America, you become black. Stop arguing. Stop saying I’m Jamaican or I’m Ghanaian. America doesn’t care. So what if you weren’t ‘black’ in your country? You’re in America now. We all have our moments of initiation into the Society of Former Negroes. (p. 220).

In the United States, the term ‘black’ encompasses all of those with darker skin, irrespective of origin or nationality. It is a catch-all term, an inherently racist term that categorizes people based solely on their position on the light-to-dark scale. And thus, Ifemelu exposes the ridiculousness of the concept, which has no meaning apart from that which is assigned to it socially. In another one of her posts, Ifemelu asserts:

But race is not biology; race is sociology. Race is not genotype; race is phenotype. Race matters because of racism. And racism is absurd because it’s about how you look. Not about the blood you have. It’s about the shade of your skin and the shape of your nose and the kink of your hair. (p. 337)

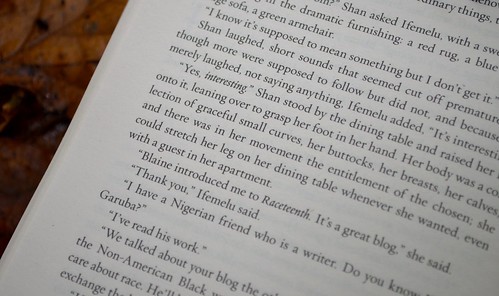

In her award-winning blog on race and racism, Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black, Ifemelu exposes all sorts of racist behavior, from euphemisms like “diversity” that people use when they are afraid of saying “race,” to accusations of “playing the race card,” to being asked to provide “the black perspective” in class, to claims that “racism is over.” But Americanah documents all sorts of racism, beyond that discussed in the blog, from the perspective of one (fictional) character’s lived experiences. From comments about black people not needing sunscreen, to the realization that white guys in college weren’t attracted to her sexually, to her numerous failed attempts to find a job when she first arrived, Ifemelu recounts how, above all else, racism shaped her life in America.

Oppression Olympics is what smart liberal Americans say to make you feel stupid and to make you shut up. But there IS an oppression olympics going on. American racial minorities – blacks, Hispanics, Asians and Jews – all get shit from white folks, different kinds of shit but shit still. Each secretly believes that it gets the worst shit. So, no, there is no United League of the Oppressed. However, all the others think they’re better than blacks because, well, they’re not black.” (p. 205)

Calling race one of America’s pivotal tribalisms — alongside class, ideology, and region — Ifemelu reveals how race shapes every single interaction Americans have with each other, and informs policy, marketing, housing, and education. Intersectionality can be a difficult thing to articulate in a casual way, but Ifemelu makes progress in this direction by demonstrating how her particular demographic characteristics — black, female, African, immigrant, relatively little money — conspire to make her first few months in America very difficult indeed. One of the most disturbing parts of the book comes during this section, and involves Ifemelu having to make a desperate decision in order to pay her rent. Her dignity is permanently compromised as a result.

‘You’re so beautiful,’ a man told her, smiling, his teeth jarringly white. ‘African women are so gorgeous, especially Ethiopians.’ (p. 169)

There was a certain luxury to charity that she could not identify with and did not have. To take “charity” for granted, to revel in this charity towards people whom one did not know—perhaps it came from having had a yesterday and having today and expecting to have tomorrow. She envied them this… Ifemelu wanted, suddenly and desperately, to be from the country of people who gave and not those who received, to be one of those who had and could therefore bask in the grace of having given. To be among those who could afford copious pity and empathy. (p. 169-170).

Nathan had told her, some months earlier, in a voice filled with hauteur, that he did not read any fiction published after 1930. ‘It all went downhill after the thirties,’ he said.She had told Blaine about it later, and there was an impatience in her tone, almost an accusation, as she added that academics were not intellectuals; they were not curious, they built their stolid tents of specialized knowledge and stayed securely in them. (p. 323-4).

Ifemelu’s primary problem with academics seems to be their overeagerness to condemn things, to accept that every problem is a result of orchestrated oppression, that only by living principally can they escape the conspiracies surrounding them. Furthermore, she finds the specialization of knowledge itself problematic, because it seems to lead to insular thinking. Many of the academics she meets, including Blaine, are self-righteous in their indignation, and consider themselves the liberated few who really know how the world actually works. The irony, of course, is that Ifemelu, with her myriad lived experiences of racism, often does a better job articulating things in her semi-casual blog than do the academics she encounters in both professional and private settings. While I don’t think that all academics are like the ones portrayed in Americanah, I do agree that self-righteousness is a slippery slope for those who work in the analysis, production, and dissemination of knowledge.

There were people thrice [Ifemelu’s] size on the Trenton platform and she looked admiringly at one of them, a woman in a very short skirt. She thought nothing of slender legs shown off in miniskirts — it was safe and easy, after all, to display legs of which the world approved — but the fat woman’s act was about the quiet conviction that one shared one with oneself, a sense of rightness that others failed to see. (p. 8)

Ifemelu stood there mesmerized. Obinze’s mother, her beautiful face, her air of sophistication, her wearing a white apron in the kitchen, was not like any other mother Ifemelu knew. Here, her father would seem crass, with his unnecessary big words, and her mother provincial and small. (p. 70)

For the most part, Ifemelu does not allow herself to feel threatened by other women (for departures from this sentiment, see the section “Incongruous Ending,” below); she is capable of recognizing and deriving pleasure from both her own appearance as well as being complimentary of others.

Happilykinkynappy.com had a bright yellow background, message boards full of posts, thumbnail photos of black women blinking at the top. They had long trailing dreadlocks, small Afros, big Afros, twists, braids, massive raucous curls and coils. They called relaxers ‘creamy crack’. They were done with pretending that their hair was what it was not, done with running from the rain and flinching from sweat. They complimented each other’s photos and ended comments with ‘hugs.’ They complained about black magazines never having natural-haired women in their pages, about drugstore products so poisoned by mineral oil that they could not moisturize natural hair. They traded recipes. They sculpted for themselves a virtual world where their coily, kinky, happy, woolly hair was normal. And Ifemelu fell into this world with a tumbling gratitude. (p. 212)

‘So [there are] three black women in maybe two thousand pages of women’s magazines, and all of them are biracial or racially ambiguous, so they could also be Indian or Puerto Rican or something. Not one of them is dark. Not one of them looks like me, so I can’t get clues for make-up from these magazines. Look, this article tells you to pinch your cheeks for colour because all their readers are supposed to have cheeks you can pinch for colour. This tells you about different hair products for everyone–and ‘everyone’ means blondes, brunettes and redheads. I am none of those.’ (295).

As Ifemelu demonstrates, the majority of American advertising contains not-so-subtle undercurrents of racism and classism. The assumption is that the women to whom these products are being advertised all share the same (relatively light) skin color, thus belying a certain expectation in regards to class and financial ability to purchase the products in question. Ifemelu is critically aware of and proud of her appearance, despite the fact that it defies American (i.e., white) beauty standards, and is a benchmark of her self-confidence. As Obinze repeatedly remarks, Ifemelu’s self-assuredness is a major factor in her intimidating appeal.

Overall, these examples are but a few of the ways in which feminism is incorporated into the book, and a full-scale study of these elements would certainly be worth an academic’s time and effort.

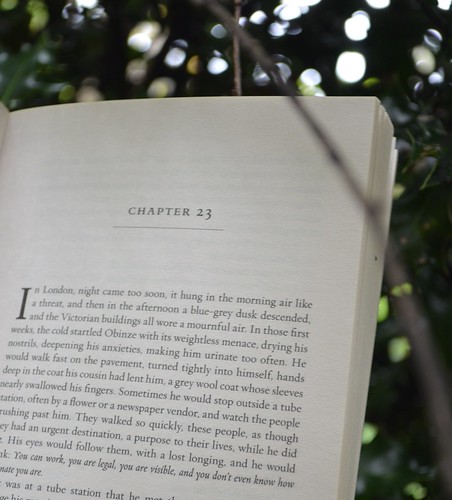

The chapters detailing Obinze’s experiences in Britain are an interesting, but inconsistent, addition to the novel. Structurally, they occupy only a small fraction of the book, around 50 pages in a 477-page story. They are less fleshed out and seemingly less important to Adichie in contrast to the minute descriptions of Ifemelu’s life in America. Adichie almost treats Obinze’s story as an afterthought, passing over his difficulties too quickly for comfort.

The undeniable heroine of Americanah is Ifemelu. The significant amount of time spent on describing her transition to life in America, her decision to return to Nigeria, her relationships and insights are the outstanding aspects of this book. Obinze is a presence in Ifemelu’s life, but not entirely relevant for the many years they remained out of touch. To truly do justice to both characters, Adichie could have either eliminated Obinze’s time abroad or more explicitly explained his time in Nigeria. Organizationally, as well, the Britain chapters could have been better integrated into the narrative. If Adichie had two separate, linear stories – Ifemelu’s and Obinze’s – and a concluding section that detailed their reunion in Nigeria, the relevance of Obinze’s story would have been better understood.

Still, it is interesting to see the way in which Adichie distinguishes between the United States and the United Kingdom. Both are built on tribalisms, she argues, but while America’s primary distinguishing characteristic is racism, the UK’s is xenophobia. Broadly speaking, the United States is not anti-immigrant (though, certainly, there are exceptions to that rule, especially concerning undocumented Mexican immigrants), but it does assign social worth based on the color of one’s skin. Conversely, the UK is less preoccupied with skin color, but abhors and resents immigrants. As Obinze reflects, Britain’s xenophobia is effectively a denial of history.

The wind blowing across the British Isles was odorous with fear of asylum seekers, infecting everybody with the panic of impending doom, and so articles were written and read, simply and stridently, as though the writers lived in a world in which the present was unconnected to the past, and they had never considered this to be the normal course of history: the influx into Britain of black and brown people from countries created by Britain… It had to be comforting, this denial of history. (p. 258-9)

This denial of history regarding immigration flows is a common facet of anti-immigrant narratives in all of the major Western countries, and finds expression in micropolitics as well. For example, after the Northern United States demolished much of the Southern United States during the Civil War, thousands of African-Americans flocked to Northern cities. Instead of being well-received by those who were theoretically opposed to slavery, many African-Americans were segregated into the poorest and least desirable areas and reduced to occupying the lowest levels of labor hierarchies. But I digress.

Eventually, Obinze is deported back to Nigeria after attempting to wed a British citizen for residency. He is acutely embarrassed, largely because he thought his middle-class background meant he would be successful in Britain. He returns, eminently humbled, and, like Ifemelu, experiences a partial loss of identity.

Perhaps the greatest weakness in Americanah, though, was the ending. Seemingly incongruous with the tone and plot of the rest of the novel, the final chapters of Americanah are undeniably romantic in nature. However, the concluding chapters set in Nigeria are interesting insofar as they examine how Ifemelu was altered during her time in America. It’s impossible to live in America, inundated with advertisements and commercialism and passive aggressiveness, without undergoing significant personal change. Upon her return to Nigeria, Ifemelu reclutantly acknowledges that she has been, to some extent, corrupted by her stay in America. She attends a partly for the “recently returned” Nigerians who have spent extended periods of time abroad, and is disappointed to find that she has become used to the foods, conversation, and ease associated with the American lifestyle.

An unease crept up on Ifemelu. She was comfortable here, and she wished she were not. She wished, too, that she were not so interested in this new restaurant, did not perk up, imagining fresh green salads and steamed still-firm vegetables. She loved eating all the things she had missed while away, jollof rice cooked with a lot of oil, fried plantains, boiled yams, but she longed, also, for the other things she had become used to in America, even quinoa, Blaine’s specialty, made with feta and tomatoes. This was what she hoped she had not become but feared that she had: a ‘they have the kinds of things we can eat’ kind of person. (p. 409).

These small differences – food, lifestyle, and conversation – conspire to make Ifemelu feel like something of a stranger in her own nation. Overall, I’d argue that Ifemelu experienced a phenomenon of displacement; she spent enough time abroad to feel alienated in her home country, and, conversely, would never feel fully integrated in the U.S.

Oddly enough, though, it was the way that Ifemelu casually picked up her relationship with Obinze — arguably the very reunion that the entire novel was working towards — that irked me the most. Apart from the obvious — i.e., that Ifemelu had spent years in America, was clearly changed, and was hardly the same person who Obinze knew as a student — there was a certain fairy-tale quality about the romantic ending of the novel. After the brutal honesty and insight contained in hundreds of Americanah’s pages, the sugary-sweet ending seemed like it was being delivered with the audience’s wishes in mind rather than Adichie’s token realism. It was also frustrating that Obinze was permitted to be the superior one. Why didn’t Ifemelu question him about the origins of his wealth? Why did Obinze get to make the final decision regarding their relationship? Why did he seemingly have all of the power, and all of the dignity? There was a reversion away from feminism in the conclusion of their relationship, a disappointing ending for a character who had exhibited such independence and self-awareness throughout the rest of the novel.

Oddly enough, though, it was the way that Ifemelu casually picked up her relationship with Obinze — arguably the very reunion that the entire novel was working towards — that irked me the most. Apart from the obvious — i.e., that Ifemelu had spent years in America, was clearly changed, and was hardly the same person who Obinze knew as a student — there was a certain fairy-tale quality about the romantic ending of the novel. After the brutal honesty and insight contained in hundreds of Americanah’s pages, the sugary-sweet ending seemed like it was being delivered with the audience’s wishes in mind rather than Adichie’s token realism. It was also frustrating that Obinze was permitted to be the superior one. Why didn’t Ifemelu question him about the origins of his wealth? Why did Obinze get to make the final decision regarding their relationship? Why did he seemingly have all of the power, and all of the dignity? There was a reversion away from feminism in the conclusion of their relationship, a disappointing ending for a character who had exhibited such independence and self-awareness throughout the rest of the novel.

I was interested in the part about the differences between the USA and the UK. Right now were having our general election here and immigration has been a hot topic. Basically we have parties blaming immigration for lack of jobs and homes to disytract from the fact that the financial services industry fucked the entire country. Its quite scary.

Yeah, just saw that Cameron vs. Miliband post on your blog! According to your poll it seems that Cameron will be the winner. Always tough to oust an incumbent, eh? But that is pretty scary about immigrants being used as the scapegoat for the powerful financial services industry (it’s not something I realized was happening, but I’m sure the same case could be made in the United States!). In general my impression of Europe as a whole is that it’s very anti-immigrant, both towards immigrants from poorer Eastern/Southern European countries moving to Western Europe, and towards immigrants from outside of Europe. It’s not just Europe, though. I’m sure you’ve heard about the anti-immigrant riots in South Africa, and even here in New Zealand people are pretty biased towards immigrants from Asia. It’s just fucked up!

Poor Ed Milliband just seems like a harmless geek. He’s likeable but doesn’t have many leaderlike qualities. I could never vote conservative though, I’m a bit of a socialist so I’ll probably vote for Ed. He’s nicer to the poor and disabled.

The main fear of the anti-immigration people is all of the eastern Europeans that come here. I guess it’s a fear of losing their culture which is silly as the UK has always stolen other cultures, usually by force! For instance the national dish here is now Chicken Tikka Masala. I’ve seen what’s happening in South Africa and it’s incredibly frightening. I don’t know what the solution is and I’m glad I’m not the person who has to come up with one! The thing is we were all immigrants at one point!

Saw the UK election results come through last night, sorry it didn’t go the way you would have preferred! Kind of shocking, actually… it seems that conservatism is on global upward swing at the moment. I mean I don’t have to even mention the Tea Party in the United States, or the New Zealand First party over here.

Fear of “losing their culture” is such a silly excuse, I agree! (And tikka masala is absolutely delicious. In fact generally speaking “New Zealand food” is fairly bland; whenever we eat out – which is rare because restaurants are freaking expensive here – we always go for Thai, Indian, Chinese, Mexican, etc.) Anyway, on the culture thing, people often speak of a loss of “social cohesion” when discussing immigrants. It’s basically one of the many euphemistic ways of saying “I don’t like people who grew up in houses that smelled different from mine.” Very frustrating.

I really enjoyed Americanah too.

Glad to hear it! I think Ifemelu is going down in history as one of my all-time favorite female protagonists.